Fair Observer Interview.. on representing diversity, aiming high and the joy of children's publishing

I was recently interviewed by Kourosh Ziabari for Fair Observer about my experiences of children's publishing.

You can read the full article here.

Here's an extract:

Ziabari: What do you think is missing, or lacking, in modern children’s literature that you try to make up for in your books?

Hart: Here in the UK, our society is becoming increasingly diverse and multicultural, but that diversity is not adequately reflected in the books our children read. When I first started writing, I did not specifically set out to look at diversity in books, it’s just something I became aware of as I got more familiar with the world of children’s publishing. So I started asking for some of my characters to be non-white. And I was surprised at the response I got — publishers were wary and unwilling. I was told that, although editors felt it would be nice to do this, sales departments were reluctant because they felt books with non-white protagonists would not sell.

These conversations were not about books I was trying to sell; the discussions were about books that I had already won contracts for. Nor was it because the subject matter of the books was controversial. It was purely because publishers felt, at that time, that my suggestions and requests would make the books less saleable, and there were, no doubt, many sales figures to backup these beliefs.

Publishers walk a very difficult line at times and issues like this are not easy to address. They invest heavily in the production of books — picture books in particular are very expensive to create and print, so publishers have to be confident they will get a return on their investment. They must sell books to survive in what is becoming an increasingly competitive and saturated market. So it’s understandable that introducing an element that might reduce sales could be an unacceptable risk.

At the same time, publishers know they have a responsibility to publish good books. Every editor I’ve ever met, without fail, has been full of passion for the work they do, and many feel their hands are tied in this regard. But as an industry, I feel we have a duty to push this agenda and continue to aim for equality of representation because this ultimately brings equality of aspiration and of opportunity. And I believe now that things are, slowly but surely, moving in the right direction.

Many publishers get round the issue of representing different ethnic and cultural backgrounds by using animal instead of human characters, but I feel this really is just a cop out. I strongly believe that children need to see themselves in books, and studies show that children learn more moral lessons from books with human characters than from books with anthropomorphised animal characters.

I spend a lot of time in schools, promoting a love of books and inspiring children to read and write creatively. Many of the children I work with are from non-white, non-European backgrounds, and yet they are still very underrepresented in our children’s literature. These children need to find characters they identify with. How can we expect them to love reading if they feel that their own identities are not valued or included, or talked about?

In a recent study, the Council for Literacy in Primary Education reported that of the 9,115 children’s books published in the UK in 2017, only 391 featured black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) characters. That’s just over 4%. Only 1% of children’s books had a BAME main character. One percent. Given that, according to the Office of National Statistics, around 14% of citizens in England and Wales are of BAME origin, these figures are grossly inadequate, and our literature is currently failing to represent one in seven of our children.

And it’s not just ethnicity that is under-represented. At the same time I was beginning to ask about ethnic diversity, I was also asking for better representation of females in my books. In 2007, I was told by one publisher that it was better to have a male protagonist because girls would read books with a male hero, but boys wouldn’t read books with a female in the lead role.

I have no doubt that this has been true in the past, but personally, I believe this is down to the way female characters have been presented in fiction. Take Enid Blyton’s The Famous Five, for example — a series that myself and many of my contemporaries were raised on, and one which is now being republished by Hodder Children’s Books. In these stories, the two most interesting characters who see most of the action are male. Of the two female characters, one is portrayed as weak, frightened and reticent. Not much to love there. The other, George, is portrayed as a tomboy, so she’s not a real girl. The boys even tell here she’s “almost as good as a boy”!

Thankfully, this overt sexism is now largely absent from modern children’s literature, but the legacy of this view still overshadows decision-making. The view that boys will not read a book with a female main character pervades because female characters in general have been given lesser or fewer roles. If our females characters are represented as strong, feisty, funny and capable, they stand a much better chance of attracting male, as well as female readers.

I have written a series of princesses books, illustrated by Sarah Warburton and published by Nosy Crow, which feature strong females in the lead role. These are not the princesses that I was brought up with, who need rescuing by brave princes; they are intelligent, feisty girls who find solutions to their own problems, and everybody else’s. I’m pleased to say that these books are selling really well, and that when I’m in schools, boys love the stories just as much as the girls do. Sadly, though, at the end of the day whilst selling and signing books for children to take home, I have heard the odd parent telling their boy-child, “Oh, you don’t want that book do you? Isn’t it for girls?” So far the child has won their parent over, so that tells us something!

Diversity is not just about race or gender either. Children’s literature is still lacking in non-typical family structures like single parent, gay parents, grandparents raising grandchildren and characters with disabilities. Of course, every book cannot contain every type of person! Picture books typically have between one and four main characters, and to expect every book to have “one of each” is unrealistic. But the industry as a whole has a responsibility to be representative overall, which means commissioning editors and designers need to look at their list of titles as a whole, to ensure that the diversity of characters is available across their list.

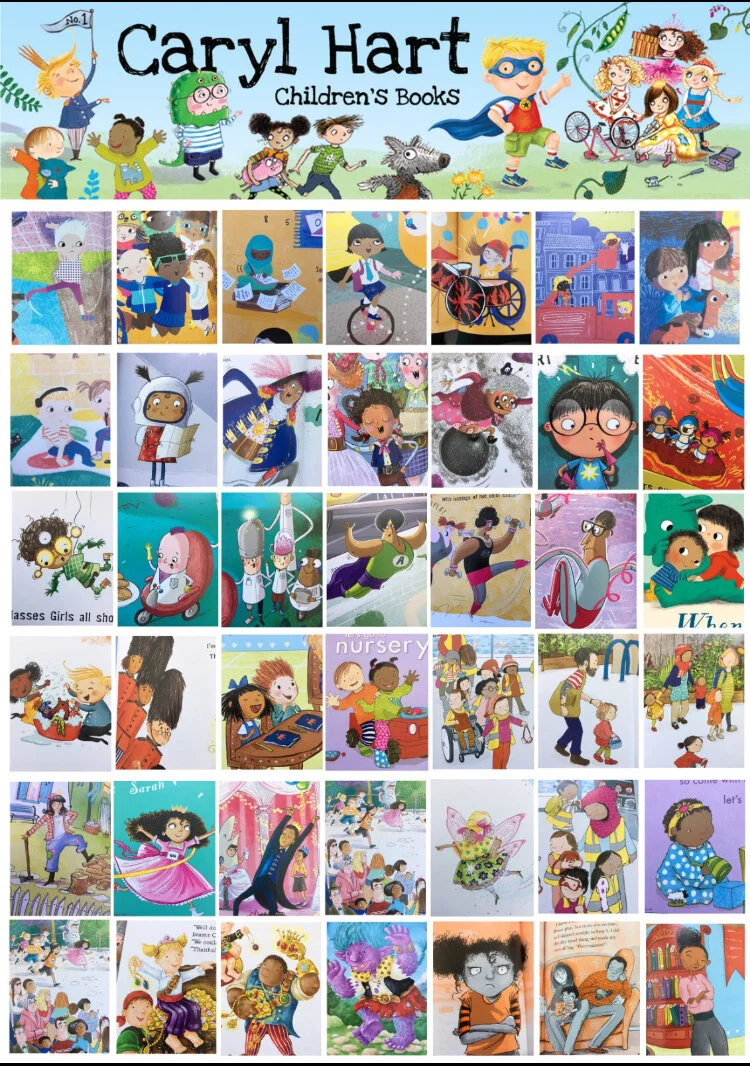

I’m pleased to say, however, that over the past eight years I have noticed that these conversations are becoming easier, and that editors are now much more open to a more diverse array of human characters. I hope that my own books go a small way into redressing this imbalance too — it’s something I now deliberately question for every title I’m lucky enough to have published.

There’s my latest book, Girls Can Do Anything. This is a book aimed at very young children and is basically a list of all the things girls, and women, can do. It is a celebration of achievement and is the most diverse book I’ve ever written, thanks to the support of my publisher, Scholastic, and the wonderful illustrations by Ali Pye. This book includes a huge array characters with different skin tones, clothing choices, hairstyles, disabilities, hobbies and careers. It includes two galleries of inspirational women from all over the world who have excelled in science, medicine, social justice, sport and business, and I’m hugely proud of what we have achieved.

Ziabari: There are numerous award-winning, best-selling children authors who continue to write and publish new works frequently. What should the parents or the children themselves take into consideration while selecting the best books to read? What are the qualities of a good, compelling, entertaining and informative book for children?

Hart: Most people will have heard of J. K. Rowling and Julia Donaldson. These have become household names in children’s literature, and rightly so. Both are brilliant writers who have created some of our best-loved stories and imaginary worlds. Their books are prominently displayed and enjoy great sales as a result. We buy what we know we’re going to like.

But the world of children’s books is rich beyond the imagination, and there is a huge selection of books out there that I would urge all parents, carers and children to try. If you’re not sure what to read, there are loads of great book bloggers online these days who review new titles and pick out the best of the best for you. Go to your local bookshop or library and take the time to have a good old browse. Most children’s sections have games areas or reading corners to keep your little ones entertained while you look. If you like a particular author, ask the sales assistant or librarian to suggest other similar stories to try.

Once a child or an adult discovers a book they like, it’s natural to want to read other books by the same author. We like what we know. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. It’s actually a great thing to do in my opinion, as you can see how that writer has developed over time, identify common themes in their stories and generally feel like you are getting to know them as a person.

But it’s also important to try new things. Pick something random off the shelf and read the first page or two. If you like it, keep reading. If you don’t, put it back and pick another one. There is nothing to lose by trying something new and everything to gain, especially if you’ve borrowed the book from a library for free! There’s no magic formula to say which books are compelling, entertaining and informative. Each book will speak to each person in a different way. Some people will love a book, while others might hate it. Lucky for us, then, that there are so many to choose from.